Symposium-fest at SFMoMA

For a museum that’s closed for construction, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has been very active. Their tagline says it all: “We’ve temporarily moved…everywhere.” One recent weekend SFMoMA was, indeed, all over San Francisco. They launched two symposia, both free and open to the public: Visual Activism (March 14-15) addressed the visual forms that inspire activism, and, inversely, the way activists use visual forms; Bearing Witness (March 16) considered the field of photography as we know it today—especially how phenomena such as social media, digital cameras, and amateur photojournalism have transformed our relationship to everyday events. The dual symposia, designed to be in dialogue with each other, intersected on a number of topics, from the use of digital technology for activist purposes to lending a voice to the silenced.

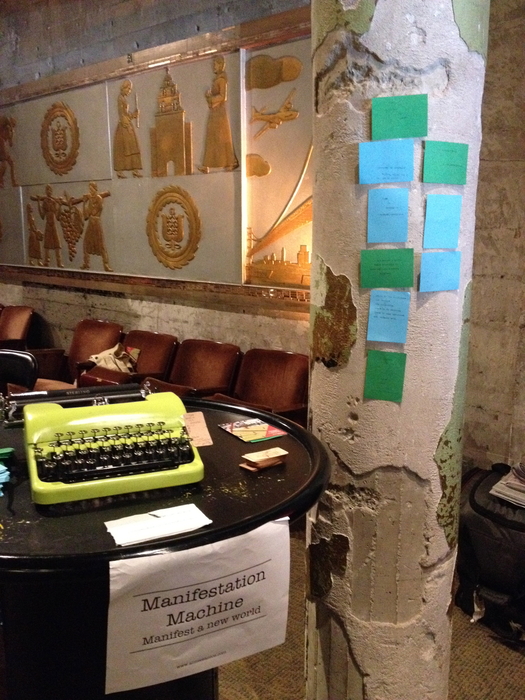

The festivities kicked off Friday morning. After walking five blocks down Mission District’s 24th Street (a flavorful Latino neighborhood on the road to gentrification), I entered Brava Theater, the venue for Visual Activism. A lime-green typewriter in the lobby, labeled “The Manifestation Machine,” had a come-hither effect. The artist, Aimee Santos, had left a note on the machine encouraging attendees to “manifest a new world.” Her instructions: type a message onto a piece of card stock, adhere it to the neighboring pillar, and you’ve done your part. Already I was pushed to be an active participant in a social art performance.

Among the Visual Activism presenters were artists, activists, and scholars—many of them a combination of these—who, together, cast a wide net of issues and tactics. Themes ranged from AIDS awareness to poverty, LGBTI issues to immigration reform, environmental justice to conflict zones. Some presentations were less relevant than others: one scholar’s interpretation of Tracey Moffatt’s photography from a queer perspective was insightful but would have better served an art history conference. Some artists should have been granted more time on stage, particularly Teddy Cruz and Favianna Rodriguez. The two artists-in-conversation not only had dynamic chemistry that made for a stimulating discussion, but their activities blend a potent mixture of visual culture and activism. Cruz, renowned for his work on the Tijuana-San Diego border, considers the benefits of artistic experimentation in marginal neighborhoods and how architecture can transform border conflict zones. Rodriguez spearheaded Migration is Beautiful, a project that uses visual material such as posters and murals to rebrand the immigration movement and promote immigrant’s rights.

Favianna Rodriguez, Logo for Migration is Beautiful, graffiti mural. Visual Activism Symposium, SFMoMA, San Francisco.

If you chose to join one of the clinics following the presentations on Day 1, your chances of remaining a silent observer dwindled. (To the chagrin of many attendees, all seven clinics were parallel sessions.) My site of choice was the Will Brown Gallery in the Mission District, host of artist Anna Moreno’s event Radical Colophon. Staged at different sites across the globe (Amsterdam, Seoul, Barcelona), Radical Colophon tackles the recent tendency to judge visual activist approaches from an ethical standpoint rather than an aesthetic one. Moreno’s events therefore place emphasis on artistic format, in this case taking the form of a food-mediated social performance. The site-specific theme? Gentrification. Moreno’s collaborator, Maggie Lawson, a local artist and chef, staged an act of appropriation to drive home the theme by turning a humble burrito into haute-cuisine by adding truffle oil, Spanish smoked paprika, and micro Swiss chard: yuppie embellishment at its finest. This served as a prompt for visitors to share their thoughts on gentrification at an open mic; listeners were encouraged to respond via Twitter using the hashtag #radicalcolophon. (A computer was provided for just this purpose.) With the Twitter feed being projected onto the gallery wall, the event felt like a multi-layered dialogue between speaker, Tweeter, and audience—physical and virtual. It was touching and revealing to hear personal battle stories about gentrification, an issue that resounds far beyond San Francisco’s borders.

Anna Moreno, Radical Colophon (detail with Maggie Lawson). Visual Activism Symposium, SFMoMA, San Francisco.

The documentation of art has been the subject of great debate in recent decades: how does one capture an art performance; an event like Radical Colophon? For Moreno, Twitter serves as a sort of documentation device, a complement to photography. But still, neither Twitter nor photography nor even video are fit to capture every moment of a performance. This is why experiments in multi-platform archiving have become increasingly important to performance artists. (Objects of a more static nature, like traditional painting and sculpture, are less challenging to document.)

These questions shine a light on the very nature of documentation, not just for artistic events but for historical ones. Some artists are merging the two: take, for instance, artist Emily Jacir’s commemoration of the expulsion of Palestinians in 1948, a catastrophic event central to the formation of Israel. Among the atrocities committed was the Israeli looting of tens of thousands of books from abandoned private libraries and homes. Today only 6,000 of these books are accounted for, and they are housed in the Jewish National Library as “abandoned property.” The books, relics of a horrific event, have been left to float in a sort of purgatory, not part of the library proper and virtually inaccessible. Jacir elegantly confronts the dark history between Israelis and Palestinians in her project ex libris (2010-2012), a memorial to the stolen property and the ignition of a longstanding conflict in that fateful year.

Emily Jacir, ex libris, installation detail (2010-2012), a project for dOCUMENTA (13). Visual Activism Symposium, SFMoMA, San Francisco.

Emily Jacir, ex libris (2010-2012), AP (40a). Translation: “Salwa Abu Rahme the Syrian British School and House of Female Teachers, Beirut. Nov. 4, 1931.” Visual Activism Symposium, SFMoMA, San Francisco.

Photography is integral to the documentation of life in conflict zones; this purpose has existed almost since photography’s inception. (Photographer Roger Fenton was commissioned to document the Crimean War in 1853, producing the first extensive photo-documentation of any war.) Film, too, has become an important source of documentation. Syrian youths today are using the camera to record the violence in their country, an approach known as guerilla filmmaking. Artist Elisa Adami considers what our responsibility is to this footage, especially since many of its creators have been killed (some during the process of filming). How do we read these images without betraying the filmmaker who risked their life for them? How can we remain discerning when we look at these images, reminding ourselves that they reveal only slivers of truth?

Photography is vital to exposing issues that are cast beneath bigger shadows. Pete Brook, who writes for Wired.com’s Raw File blog and for Prison Photography, considers photography’s role in prison reform. For many, prisoners carry a stigma of sub-humanity that is debilitating and merciless, and many activists have tackled this social and political neglect through photography. The project Tamms Year Ten, prompted by the horrendous treatment of inmates at the super-max prison in Illinois (now closed), invited prisoners—all of whom were in solitary confinement—to request a photograph of their choice to be sent to them. Here is an example of one such request:

A grey & white (mix) “Warmblood” horse(s) in an outdoor environment — shown in action, such as rearing up or jumping or climbing. I’d like the photo to convey freedom, strength, and the wisdom of nature.

Additional instructions: If possible, taken in a cold environment so that clouds of hot breath can be seen.

It’s hard not to liquefy after reading this; the prisoner’s sense of deprivation is so patent as to inspire a visceral awareness of things that we take for granted, like “clouds of hot breath.” The essential humanity of this prisoner is clear; he craves freedom and nature and movement.

Josh Begley, on the other hand, takes a macro approach to prison reform, using photography to capture the geography of incarceration in the United States. His project, Prison Map, culls together aerial photos of prisons, prompting us to consider the abundance of prisons in our country and, most importantly, ask: why so many?

Josh Begley, Prison Map (Facility 226). Google Image. Visual Activism Symposium, SFMoMA, San Francisco.

As a symposium on activism is wont to do, I was galvanized to hand down the many ideas and messages culled from such a wide variety of projects. If you wish to see a list of annotated links to organizations and projects, click here.

by Olivia Fales

in Focus on the American West

Apr 1, 2014

You are an incredible writer. The way you write and express yourself helps the reader to visualize what you are discussing. Wow! Way to Go: Love, A very impressed mother

Olivia, you are an incredible writer. Your words are like delicious chocolate cake. The more you eat, the more you want. However in the case of your writing, the more you read, the more you want. Thank you so much for the joy of your words. With Much Love, A very proud mother

Heya i am f?r th? first time here. I c?me acro?s this board and I

find It really useful & it ?elped me out a lot. I hope

to give somet?i?g back and hel? others like you aided m?.

That’s such a pleasure to hear– I’m honored! What in particular helped you? Thanks for reaching out.