Interview with Hera Büyükta?ç?yan on Armenity, Venice Biennale

I had the chance to interview my friend Hera Büyükta?ç?yan, who is one of the youngest artists showcased at “Armenity“, the exhibition presented by the Armenian Pavilion, winner of the Golden Lion at the 56th Venice Biennale. Here’s what Hera Büyükta?ç?yan told me about her two artworks on show at the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, Venice.

Eleonora Castagna: How did you end up joining the project Armenity? How did Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg present the curatorial statement to you?

Hera Büyükta?ç?yan: I have been invited to Armenity through Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg last Summer, and she presented me the context of the exhibition, which was really exciting for me to be a part of. Through the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, the project brings together 18 artists of Armenian origin of different generations from all around the world, who experienced the notion of Armenity in different terms and approaches. The exhibition aims to question how we unfold an identity, memory or history whilst revealing invisible narratives to future audiences as well as healing the past. Armenity is more like a wide range reflection on a state of being with its multiple layers, rather than a limited perspective on history. The exhibition takes place at the Mekhitarist Congregation on the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, which truly carries the real essence of Armenity, as a treasure island of intellectual knowledge, culture and richness of language. In this sense, witnessing the togetherness of a dispersed identity coming together via the togetherness of these 18 artists on one utopian island has been deeply meaningful for me.

E.C. In your work, you have always addressed the themes that now are at the core of the exhibition at the Armenian Pavilion: displacement and territory, justice and reconciliation, ethos and resilience. One of your main themes, however, is memory. How did you choose to present these themes in your artwork for “Armenity”?

H.B. In a sense, through Armenity I got the chance to be able to unfold my own personal history and my relation with my identity, and experience the parts of it that were unknown to me. My relation with the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni started growing from the moment I first visited it in 2013, and as a person who has graduated from one of the Mekhitarist schools in Istanbul my interaction with the island was very deep and personal. I began to question many things about Armenity. For instance, that was the first time I realized my deep connection with my language, that suddenly got revealed from the moment I stepped on the island. Although I use Armenian in my daily life, I was often thinking that I had a weak connection with language and had been reciting this saying of my grandmother, If you lose your language, you lose your identity!. So in a sense language became a tool for me to discover many invisible aspects deep down within the memory of the island, as well as myself as an island. Islands are actually very utopian places. They are completely surrounded by water, and the only way one can connect to the rest of the world is by sailing across it. Its a utopian space because it imbibes forgotten elements of memory and knowledge. In the case of San Lazzaro, it preserves everything about Armenity within itself, especially knowledge and culture. The journey of Mekhitar, an Armenian monk who founded the Mekhitarist Congregation in 1717 on the Island of San Lazzaro, began back in Anatolia in Sebaste (Sivas). They carried with them the Armenian culture, language and knowledge, with the dream of conveying it all into an educational center and a printing house, since printing is one of the most important practices in the Armenian culture. The printing house within the island is another important instrument that immortalizes oral history into something written and physical, that reaches out to future generations through books and documents. Last but not least, the island has also welcomed many artists, writers, scientists and intellectuals throughout the Enlightenment period, and one can see its reflections inside the monastery. In this sense, the island as a whole has become a cabinet of memory for me, where I was able not only to experience the true sense of Armenity, but also to discover the unknown parts of each and every aspect of this culture through the island as a storyteller itself.

E.C. During the process of creation of the works, did you have the possibility to discuss, dialogue or compare with the other participating artists? What did this comparison give to you?

H.B. During the production phase, I have been in contact with two of the artists from the show. We were sharing our experiences whilst dealing with certain fragments of the past. The main interaction with most of the artists happened during the preparation of the exhibition on the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, which was truly unique for me. For me it was actually beyond a gathering of artists who speak and try to understand each other’s work it was more like an exploration of our own Armenity and understanding the invisible and long lost relations we all had with ourselves. Language was the main element that was creating this sense of belonging and making it stronger as well as creating a language atlas between us, as each one of us was coming from different geographies, and apart from Armenian many other languages were being spoken. This enabled me to see myself from a distance, and to witness this new experience that has opened a new dimension for me in terms of creating spaces out of language. Coming back to the exhibition, seeing each artwork within the monastery was more like a voyage to me, as the curator has successfully placed each work in different locations on the island . The artists created small scale cosmos at their works’s locations and had a great dialogue with the space itself. For me, experiencing this was truly unique to witness how art practices are conveyed within a living place that already holds a great spirit.

E.C. Could you explain your works to us, and the titles you chose for them?

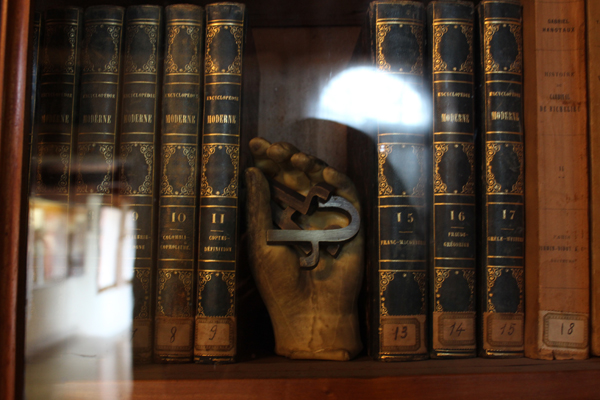

H.B. There are two pieces of mine within the show, in Lord Byrons study room. Lord Byron has studied the Armenian language at the age of 28 and has translated several books from English to Armenian. He also wrote a grammar book half in Armenian and half in English. I referenced Lord Byrons attempt to learn Armenian, which he calls the Language of Lost Paradise, with my kinetic sculpture Letters from Lost Paradise: the existence of Byron is being reenacted as if he was writing letters at his desk. The moving wooden blocks, which resemble letter stamps, also commemorate the printing history of the island, and try to revive the no longer functioning printing machines. This act is connected to the relation between oral and written histories, and to the way the printing tradition in Armenian history has had an important role in documenting/recording time and memory. The text (Letters from Lost Paradise) formed by the stamps is written in English with Armenian letters. Through this movement of the letters, the piece not only points out to Lord Byron, but also to the island itself as a utopian sphere, and of course to the many intellectuals and creative thinkers that have lived on this island from the Enlightenment era until now and, in a sense, it gives a breath to the space. The Keepers is another sculptural installation inside Lord Byrons Room, which is in dialogue with the Egyptian Mummy located in the room, a gift to the Monastery. Just as the mummy is an instrument of preserving physicality and obtaining eternal life after death, the wax-casted hands holding bronze letters and words in their palms, placed at various spots among the books in the library, work as reminders of a long lost or invisible fragment of life. I call them The Keepers because they are installed between books on the bookshelves that surround the whole room, resembling small scale monuments, or reminders that stand and welcome the audience by keeping their treasures in their palms.

E.C. I know most of your works are installations. Do you have any preference about your artistic medium?

H.B. I guess I have a certain interest in wood itself and in wooden objects, because its a lively element that still breathes, and has its peculiar voice that reveals itself according to movement. Apart from that, the second medium I often use is bronze, that I often put it in dialogue with softer materials such as wood, fabric, wax or soap. Apart from these major two, I use a big variety of materials that differ depending on the project.

E.C. What does the concept of Armenity represent to you?

H.B. Armenity is for me more than a definition of an identity, more than a state of being. Its the accumulation of time, knowledge, language, tradition, habits and a rich topography. Although it has political implications for many people, for me it is not something that can be limited to certain aspects of history. There is the tragic and heavy reality of the memory and traces of 1915, that has stayed inside people’s hearts and spirits generations long. However today, explaining what Armenity truly means can become a language that opens up a path for healing the past not completely of course, but it does partially succeed. This is because once people know about each other, and the richness of their beings and identities, the notion of otherness or the so-called xenophobia can be overcome. So, the past can be healed today by knowing ourselves!

Armenity is on view at the Armenian Pavilion winner of the Golden Lion at the 56th Venice Biennale on the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, Venice through November 22, 2015

by Eleonora Castagna

in Focus on Europe

Jun 24, 2015